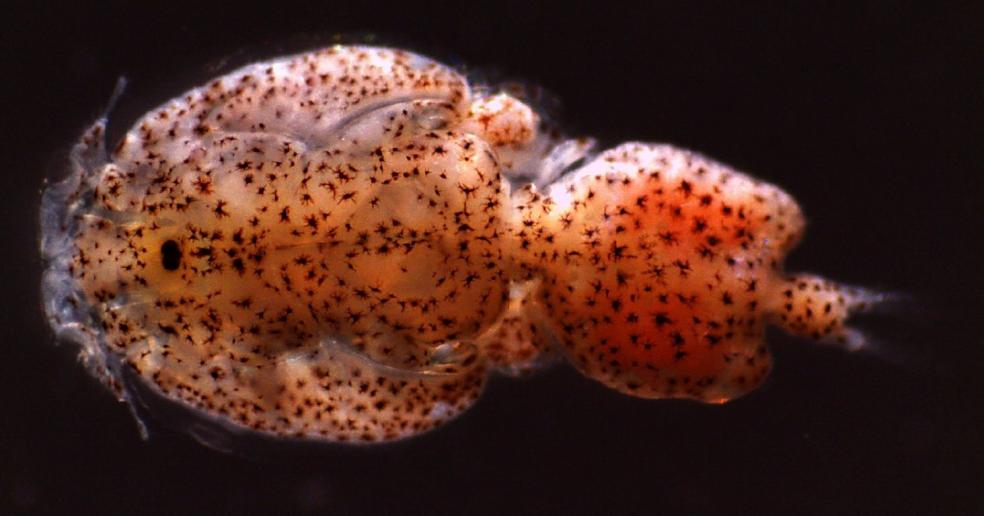

Research project launched on how sea lice are impacting salmon fisheries

Plymouth University and the Universidad de Chile are leading a new research project to investigate the issue of sea lice infestation that is costing the Atlantic salmon aquaculture industry millions of pounds in lost stock and treatment strategies.

The two year project will bring together experts across biotechnology, microbiology, immunology and pathology to study the effect that the lice have upon the salmon’s skin and gut defences, and the way it hampers physiological processes and their ability to withstand other infections.

Funded by a £385,000 grant from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, and the Chilean government (CONICYT), the project will identify the factors involved in determining salmon susceptibility to lice in order to develop effective measures to address this increasingly global issue, one that costs the UK aquaculture sector alone more than £20 million annually.

Dr Daniel Merrifield, Lecturer in Fish Health and Nutrition at the Aquatic Animal Nutrition and Health Research Facility within Plymouth's School of Biological Sciences, said: “Copepod parasites (sea lice) are a major factor limiting growth in the global salmonid aquaculture sector. Economic losses associated with infections cost the Chilean aquaculture industry in excess of US$120 million per year, and it represents a major risk for global food security.”

Current strategies to control sea lice have included the administration of a number of licensed and antiparasitic drugs, but the parasites have become increasingly resistant, leaving salmon farms vulnerable to infestation. It also threatens related industries such as traditional fisheries due to the potential transfer of infection from cultured fish to those in the wild.

Plymouth academics will work with colleagues at the Universities of Aberdeen (Prof Sam Martin), Glasgow (Dr Martin Llewellyn), Heriot Watt (Dr Ted Henry), and the Universidad de Chile (Dr Jaime Romero) and key industrial partners including BioMar, Lallemand and Veterquimica, to examine what impact the sea lice have upon the skin mucus which forms the salmon's first line of defence, and how it responds to that infestation.

Dr Jaime Romero said: “Our main goal is to explore the relationship between mucosal health, diet and microbiota in salmon, with knowledge then being transferred to other aquaculture species in the North African/Middle Eastern aquaculture sectors, including sea breams, European/Asian sea basses, mullets, and groupers.”

“Understanding both lice and salmon responses to infection will lead to the development of novel feed ingredients that will benefit the industry,” added Dr John Tinsley from BioMar.

The researchers will then look at the efficacy of dietary supplements on the fish’s immune system, the microbes on its skin and its ability to develop resistance to sea lice infestation – as well as investigating the impact of dietary supplements upon the lice. These findings will then be validated on a commercial farming scale to help inform suitable future treatment strategies for aquaculture to improve the salmon’s resistance to infestation.

Heather Jones, CEO of the Scottish Aquaculture Innovation Centre, who has previously highlighted that the control of sea lice is a high priority, said: “The project will have important implications as to what the most efficient sea louse control strategies are for Scotland and Ireland.”